Originally published in Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History (Indiana Historical Society), Spring 2023: 5-13.

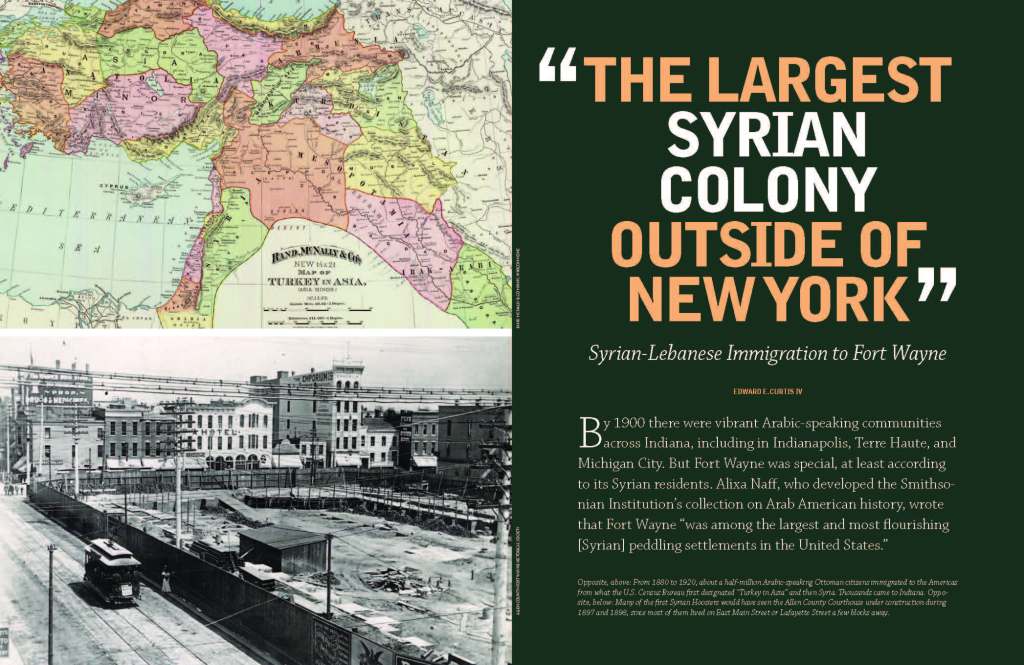

By 1900 there were vibrant Arabic-speaking communities across Indiana, including in Indianapolis, Terre Haute, and Michigan City. But Fort Wayne was special, at least according to its Syrian residents. Alixa Naff, who developed the Smithsonian Institution’s collection on Arab American history, wrote that Fort Wayne “was among the largest and most flourishing [Syrian] peddling settlements in the United States.”

The migrants who settled in Fort Wayne, like other people from Greater Syria, which includes modern-day Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Palestine, were part of a mass migration of perhaps half a million people—one out of every five Syrians—from the Eastern Mediterranean to the Americas before 1920. The reason they arrived in Fort Wayne was because it was a quickly growing community that offered economic opportunity, especially for those going into the peddling business.

Credit: U.S. Census Bureau.

Although it is difficult to estimate exactly how many Arabic-speaking people from the Eastern Mediterranean went to Fort Wayne—and even more so, how long they stayed—Syrian Fort Wayne had quite the reputation in its day. An Indianapolis Star reporter, surely exaggerating, said that it was the “the largest Syrian colony outside of New York,” writing that the population was between 225 and 250. One population estimate in the Fort Wayne Weekly Sentinel in 1894 was 100 to 120 people from fifteen to sixteen families. The 1900 census counted at least 110 Syrians, which was close to the “eyeball” estimate of 150 of the many oral histories that Naff collected; however, this was an estimate of people who lived in Fort Wayne at any one fixed point in time.

Because the peddler business was by nature itinerant, the number who migrated to and from Fort Wayne was much likely higher. For example, in an 1898 population estimate by the “Right Reverend Raphael Hawaweeny, the first Syrian Orthodox bishop in America . . . Fort Wayne ranked second with 424,” and this number only referred to the number of Orthodox rather than the Melkite, Maronite, Roman Catholic, Protestant Christians, not to mention the few Muslims, Jews, and Druze among the immigrants. According to Naff, the bishop’s list likely counted people who had come to Fort Wayne and departed. Because it was a kind of running tab of the 1890s population, it indicates just how important of a hub Fort Wayne was in the migration of Syrians to and around the Midwest.

Key to Fort Wayne’s early success as a peddling settlement was Salem Bishara. Credited in the earliest newspapers accounts of the Syrian community in Fort Wayne as the founding figure of the community, he was also remembered as such in oral-history interviews recorded over a half century later. Bishara, who became a U.S. citizen in 1896, was from Dahr al-Ahmar, a small village currently located near the Lebanese border with Syria. Many of Fort Wayne’s first Syrian citizens came from the same area, especially from nearby Rashaya, a larger town located on western side of Mount Hermon with an elevation of almost 4,000 feet. Most of Fort Wayne’s Arabic-speaking people had grown up on mountains and in valleys rather than in deserts.

Credit: WikiCommons.

The Weekly Sentinel called Salem Bishara the “high mogul of the Syrian population . . . a first-class sort of a man who tries to live up to the Golden Rule.” He opened his first store selling “importations from Damascus, Beirut, and Constantinople, consisting of tapestries, laces and rare pieces of linen.” He then became a supplier to numerous peddlers, whom he would sometimes greet as they arrived in Fort Wayne by rail to make their fortunes in the New World. He supplied them with “notions” that they could carry over long distances in their peddler packs, including such items as buttons, needles, thread, collar stays, seam rippers, and snaps.

On Mondays, according to the Fort Wayne Morning Journal Gazette, the peddlers, both men and women, traveled up to seventy miles by rail into the countryside, then they walked back to Fort Wayne, selling their goods as they went. “They trudge mile after mile down the hot, dusty highways with great packs on their backs. Their only companion is a rude walking stick,” wrote W. M. Herschell.

In 1900 more members of the community, almost all peddlers, lived as boarders in Bishara’s building at 59 East Main Street than at any other single location. Including his own family, forty-six Syrians—almost half of all the people recorded in the census that year—lived in his brick building, located in the city’s Second Ward, home to the courthouse, shops, saloons, and boardinghouses.

Credit: Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Fort Wayne, Allen County, Indiana. Sanborn Map Company, 1902.

As a symbol of success, Bishara was a target for a variety of schemes. Sometimes the peddlers to whom he extended credit simply disappeared and never paid their debts. Other times, he fell victim to embezzlement. In 1901 his bookkeeper, Michael Bosmarra, devised a plan to supply customers with free goods in exchange for a kickback. Bosmarra would ask that the money be sent to a sex worker on Columbia Street who was evidently “his steady.”

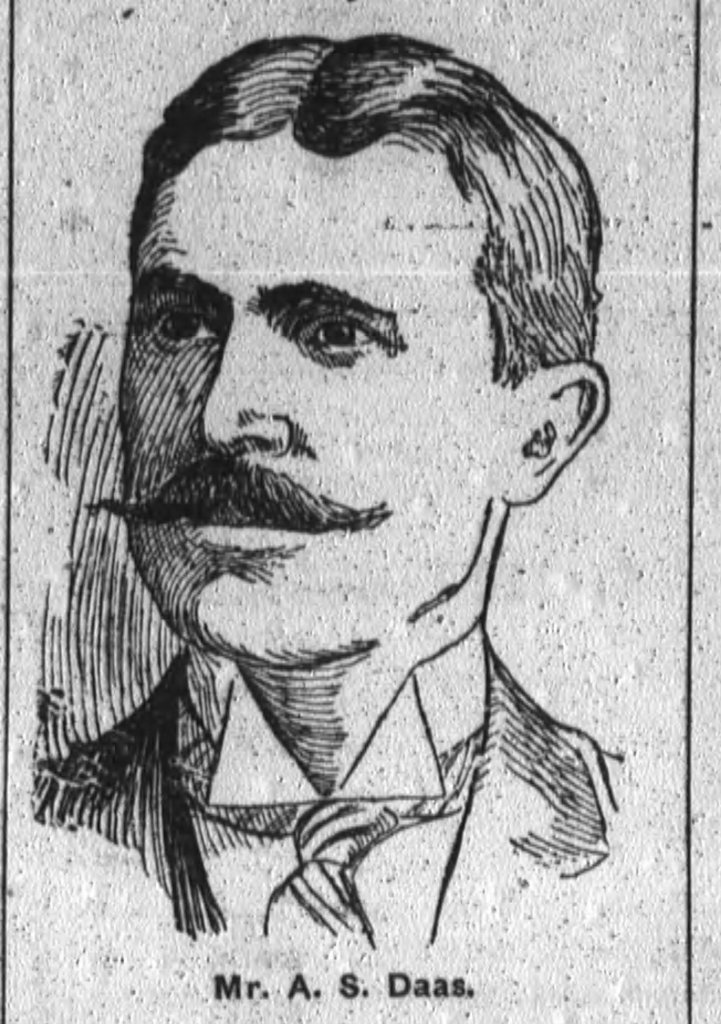

By the early 1900s Bishara had fallen on hard times and was no longer the only powerful leader of the Syrian community. A fire at his store destroyed perhaps $5,000 in merchandise. The business went bankrupt, and the district court took possession of what remained. His main rival, according to the press, was Kaleel Teen, the manager of the popular Abdallah S. Daas store on 19 Lafeyette Street. Of the 110 Syrian-born residents that the census counted in 1900, thirty-seven of them, both men and women, lived under Teen’s roof in a large three-story house.

Arabic-speaking people were a small percentage of the total population of this German-majority town of 45,000 in 1900. Nevertheless, Syrians certainly made an impression in the town’s public life. By the early 1900s, forty-six members of the community formed the Syrian Patriotic Society to encourage patriotic identification with the United States and to aid its poor members. As a voting bloc, they were credited with uniting, even though they were members of both the Republican and Democratic parties, behind the election of Democrat Henry Wiebke as city councilman from the Second Ward. Opponents labeled Wiebke “the Syrian councilman,” implying that he was beholden to a somewhat untrustworthy group of Hoosiers. Republican polling officials repeatedly challenged the eligibility of Syrian voters, but they showed up at the polls with their citizenship papers.

Because many of them were foreign-born peddlers who constantly interacted with members of the public, Syrians were a population in the public eye. Native-born Hoosiers reacted to them with a combination of prejudice, curiosity, and/or admiration. On the plus side, successful merchants such as Bishara and Teen were seen as respectable people. So were those willing to fight for their country. When in 1898 some Syrian immigrants from New York became part of Major General William R. Shafter’s volunteers and the U.S. Army’s Fifth Corps to fight in Cuba against the Spanish, one particularly brave Syrian soldier was cited as an exemplar of “someone who shows that the Syrians make as patriotic American citizens as any of our foreign-born citizens.”

There was also plenty of prejudice aimed at Syrians. Classified as racially white in the census, they were often referred to as “Orientals” in local newspapers. As such, they were seen and often treated as people of color by fellow citizens. A negative newspaper story, reprinted from the East Coast, claimed that Congress should enact immigration restrictions against the Syrians, who were dishonest, scandalous, promiscuous “pests,” a population increasing with “alarming rapidity.”

Credit: Fort Wayne Daily Gazette, January 12, 1898, 8.

The presence of female Syrian peddlers was often shocking to the middle and upper classes in Fort Wayne and across the country. In the dominant “respectable” society of the Gilded Age, the ideal woman was often seen as a person devoted to “hearth and home,” as well as to church, social clubs, and philanthropic endeavors. Public space was segregated not only by race at this time, but also by gender, and women were unexpected in the rough-and-tumble world of street-side retail sales.

Bishara’s sister-in-law, Elizabeth Bashara, née Nazha Risk, was a case in point. Born around 1883 in the beautiful mountainous village of Hasroun, today located in northern Lebanon’s Qadisha Gorge, Elizabeth left her native land around the age of eight or nine. Arriving with her father and mother-in-law first in Toledo and then moving to Columbus, Ohio, she accompanied her father on his peddling runs in the country for a practical reason. Without her, no one would offer him shelter for the night. But “when the farmers would see, a little girl, they would feel sorry for me and let us in,” she remembered.

In a couple years, Elizabeth started peddling in the city on her own: “they gave me a notions case with icons, crosses, and pictures.” One day, after a couple ladies answered her knocking at the door, they decided that Elizabeth’s clothes were shabby. “I bet if she had a nice dress on, she would look nice,” one of them said to the other. So, they took two or three hours of her work time to hem a dress and even put a sailor’s hat on her. Afterward, Elizabeth returned home to change. No one would buy anything from her if they thought she was wealthy, she said. But the ladies saw her walking without the new dress and insisted that she put it back on. Other people’s sympathy was useful to increase sales, but Elizabeth did not feel sorry for herself. “We had a lot of fun,” she said, referring to the peddling business. She relished the challenge of getting people to buy something that they did not want. It was a difficult life that included suffering, Elizabeth later reflected, but that did not make her pathetic. It made her proud.

In just three or four years, Elizabeth’s father and mother-in-law wanted to return home, but instead of taking Elizabeth with them, they decided to “marry me off,” she bluntly observed. She wed Kaleel Bishara in Springfield, Ohio, around the late 1890s. The couple moved to Fort Wayne and then, with his brother Salem’s help, to Hartford City, a town about fifty miles south that was, according to Elizabeth, “booming with gas and oil.” When the oil and gas ran out, she said, they settled permanently in Fort Wayne.

The prejudice directed toward Syrians was not always as benign as the patronizing attitudes from Elizabeth’s customers. For example, one Sunday afternoon in November 1899, Habeeb Farah was riding his new bicycle with a couple friends on Lafayette Street when “three men in a noisy state of intoxication . . . called the Syrians ‘dagoes’ and told them that they could whip any foreigner who came to town.” The boys assaulted the Syrians, using “clubs, bricks, stones” and even a beer bottle, which one man used to cut “ugly gashes in the faces of three Syrians.” But “the boys” had chosen the wrong place for the attack. Most Syrians lived on and around Lafayette Street, and several soon came to the aid of Farah and the two men. The boys were arrested and charged with assault and battery.

Sundays were an important day of gathering for the community. “Every Sunday,” remembered Elizabeth, “we would take the 9 o’clock train from Hartford City to Fort Wayne and return on the 6 o’clock train.” Since most Syrians in Fort Wayne were Christians, many would attend church. The most popular places to worship, she noted, were the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception and Saint Patrick, where many of the community’s baptisms and funerals took place. Most Syrians in Fort Wayne had been born into the Orthodox, Maronite, or Melkite Christian community, but because none of these denominations had built churches in Fort Wayne, many families attended Roman Catholic parishes, as well as Episcopalian, Presbyterian, and other Protestant congregations.

Sunday was about much more than church. It was also about eating, drinking, and dancing together. Sometimes, when the community gathered, there would be a new case of araq—distilled wine made of grapes and anise seed. Some community members would “enjoy a dance and a feast of wine” that might last for days, depending on when the araq ran out. Oral-history interviews and contemporaneous press coverage indicate that these communal gatherings among Arabic-speaking people included people from different villages, classes, educational backgrounds, and religious denominations. There were disputes among Syrians, of course, but such disputes did not seem to threaten the conviviality of these occasions.

It was different in the world outside the bounds of ethnic solidarity. In the English-speaking world, a Syrian’s class affected their life opportunities and social networks. Press accounts spoke about Syrians in two registers—one dubious of poor Syrians and one full of praise for the respectable, Christian, educated middle class. For example, Abdullah S. Daas, a Syrian Presbyterian merchant who lived in Fort Wayne during the 1890s, was described as an “able and highly educated business man. He is a fluent speaker of English and is thoroughly Americanized in his business methods and a very progressive young man.” When the Teen family hosted him and his bride for a party on Lafayette Street, the house was described as “elegantly furnished.” The ladies were “received in the rear parlor” while the gentlemen were in the front. The good taste of the Teens was evident in their decision to hold “festivities . . . of a more lively social character” on a day other than Sunday, the Sabbath.

Credit: Fort Wayne Daily News, May 4, 1904, 4.

The word “surprising” was used more than once in the newspapers to describe the English literacy of middle-class Syrian Americans. Local journalists did not know that many had studied English before leaving their country. In addition to the Ottoman-run schools where students learned Arabic and Ottoman Turkish, Christian missionaries from the United States, Russia, France, and other countries operated schools across the region. The most prestigious U.S. university was the Syrian Protestant College, founded in 1866 (it later became the American University of Beirut). People such as Daas were either literate or proficient before departing for the Americas.

Syrians in Fort Wayne were aware of the stereotyping of their community, and in at least one case, one of them asked newspapers to change it. Joe Bonahoon [Bonahoom], a fruit-stand owner, told the Journal-Gazette in 1903 that Herschell’s article on the Syrian community made it seem as if “the rank and file of the colony are led about at will by the leaders.” He argued that, while newly arrived immigrants needed help in getting a start, the community did not support the idea of “kings and castes,” adding, “As a race we have done well. We have made money and kept out of serious trouble. We like the idea of being equal and because one of us makes more than some of the rest, we do not think he is any better than the rank and file.”

Bonahoom’s words were a fitting eulogy for the former “king” of the Syrians, Salem Bishara. In 1908 Bishara’s death was front-page news in the Fort Wayne Sentinel. The paper repeated the same tired ideas about how Bishara had once been an “autocrat” and all Syrians “followed his bidding without question.” That was untrue, but the newspaper did get something right about the magnitude of his contributions to building the Arab community in Fort Wayne: “His countrymen turned to him in every emergency for advice and assistance and followed his direction implicitly in business. . . . He settled disputes and adjudicated differences . . . and new recruits were unfailingly recipient of his bounty.”

The newspaper associated the values of mutual aid and ethnic solidarity with an individual, the first de facto leader of the community, but these traditions were embraced by the Syrian community as a whole. Individuals had little hope of success if cooperation and assistance were not forthcoming from the entire group. These practical ethics led to the establishment of a community now more than 130 years old. It is the reason why some of those original families still live and prosper in the Summit City. It is hard to imagine how it would have happened otherwise.

The legacy of Fort Wayne’s Syrian community is an important reminder of how many more stories of ethnic history are left to be told in the Hoosier State. Too often assumed to be racially and religiously homogenous, Indiana’s historical archives are full of details of our shared past. There are more than traces here. There are complex, essential details about the lives of Hoosier ancestors who have shaped our life together in ways yet to be discovered.

Selected Sources Albrecht, Charlotte Karem. Possible Histories: Arab Americans and the Queer Ecology of Peddling. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2023. | Elizabeth Bashara and Joe David (Yusuf Sim‘an Daud) in Faris and Yamna Naff Arab American Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, 1962. | Brown, Nancy Eileen. “The 1901 Fort Wayne Indiana City Election.” Master’s thesis, Indiana University, 2013. | “Former Syrian Leader is Dead.” Fort Wayne Sentinel, December 8, 1908. | Herschell, W. M. “Our Syrian Colony.” Fort Wayne Journal Gazette, June 22, 1903. | Naff, Alixa. Becoming American: The Early Arab Immigrant Experience. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1985. | “Not Lead [Led] About by the Nose.” Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette, June 24, 1903.

You must be logged in to post a comment.